How a UFC Impostor Became Australia’s First NHB Event

This is the second installment of a multi-part series on the

first modern MMA show held in Australia, billed the “Australasian

Ultimate Fighting Championship.”

PROLOGUE |

PART 1 |

PART 2 |

PART 3 |

PART 4 |

PART 5

In early 1997, two organizations with the same three-letter name

began a legal skirmish which would culminate in a trademark

infringement lawsuit before the Federal Court of Australia.

For the Ultimate Fighting Championship owned and operated by Semaphore Entertainment Group in New York, this battle was one of many the organization waged at the time. After a brief honeymoon period of profitability and blue skies following the company’s runaway pay-per-view successes from 1993 to 1995, the UFC was buckling under the weight of politicians, cable operators and moralizing op-ed columnists. This was done in the name of protecting young, impressionable minds from a “lowest common denominator”—violence—which the UFC glorified above all else, proselytized then Arizona Senator and United States Senate Commerce Committee Chairman John McCain.

At the same time, on the other side of the world in Sydney, Randy Bable’s “Australasian UFC”—which he had incorporated in August 1996, with the hopes of jump starting an NHB franchise in the southern hemisphere—was navigating its own gauntlet of regulators, media naysayers and logistical hurdles ahead of its inaugural tournament event in the spring of 1997. Fervent discussions were ongoing with the Boxing Authority of New South Wales, which threatened to shut down the event, all while the eight-man openweight bracket was proving to be its own shape-shifting nightmare. Fighters dropped out left and right, and a succession of replacements were called up on short notice.

To avoid the political furor playing out in the United States, Bable aimed for what he considered a more streamlined, “professionalized” and regulated NHB product compared to SEG’s UFC. However, this was not going according to plan, and after he had already invested a quarter of a million dollars of his own money into the Sydney event, SEG fired the first salvo. The two organizations were brought into each other’s orbit via a cease-and-desist letter delivered to Bable’s office and the Darling Harbor Convention Center, where the tournament was supposed to take place in three weeks’ time.

“At this point in time, we were focused on staying alive,” recalled SEG Chief Operating Officer David Isaacs, who, alongside SEG President Bob Meyrowitz, was responsible for overseeing the company’s litany of lawsuits in America and abroad. “In the context of that, we kept having these competitors that would arrive on the scene and, in our view, potentially screw stuff up. That was what we were dealing with, and we had concerns about that from a lot of different perspectives. One was, we were focused on what we were doing as the Ultimate Fighting Championship, and we didn’t want anyone to be confused with us and put on a crappy event, or even worse, do something unsafe and get somebody hurt. That would hurt the whole sport but also our company. That was one thing that was going on around that phase. We’re scrapping for our survival, and everything we do is so, so important.”

* * *

SEG executives were right to be mindful of the impact that competing promotions could have on the UFC’s increasingly precarious fortunes. Indeed, as Isaacs was quick to point out, the UFC 12 debacle in February 1997—which saw the UFC relocate its Octagon and fighters and staff from Niagara Falls, New York, to the Dothan Civic Center in Dothan, Alabama, on 48 hours’ notice—was due to the conduct of Battlecade Extreme Fighting, an NHB upstart three events into a four-event existence.

After SEG had spent more than a year lobbying to get NHB sanctioned in its home state of New York, a statute doing so was passed by the New York legislature. It placed the UFC under the purview of the New York State Athletic Commission. The UFC tentatively scheduled an event at the Niagara Falls Convention and Civic Center, far away from the scrutiny of the New York media and with the intention of building credibility and a constructive working relationship with the NYSAC.

Reckless or indifferent to SEG’s approach, Battlecade hastily announced it would hold a show smack dab in the middle of Manhattan, drawing the ire of New York Mayor Rudy Giuliani and setting off a chain of events that led the NYSAC to issue a 111-page rule book for NHB in an obvious attempt to backtrack on the legislation. A failed lawsuit brought by the SEG against the NYSAC challenging the new regulations failed and precipitated the mad dash south. The company was out another $300,000 it did not have, and the UFC’s New York aspirations were sunk in the process.

“In the midst of all that, here are these guys in Australia,” said Isaacs, who gets animated about the subject more than two decades later, “and they’re not just running a mixed martial arts event; they are literally trying to rip us off. They are using our name. They are using our octagon. They are literally using an image from one of our fights. They’re stealing our stuff.”

As narrated in a sworn affidavit by SEG’s Australian trademark attorney Spiros Papas obtained by Sherdog, the cease-and-desist letters accused Bable’s company, “UFC Events Pty Limited,” of various trademark infringements. This included the use of the octagonal cage and logos that were nearly identical to SEG’s and, most brazenly, passing itself off as the original UFC in its promotional materials published in the Blitz martial arts magazine. Further cease-and-desist notices were sent on March 14, 1997, triggering negotiations between the SEG and Bable’s lawyers. These discussions played out against an explicit threat from SEG that, if an agreement could not be reached, it would seek an injunction to stop the event from going forward.

“In Australia, nobody knew about [the UFC],” Bable said. “Nobody knew about it. Maybe point-one percent of the population knew what the thing was, so they really couldn’t argue that it was a known branding or a known trademark here in Australia. It’s a different country to America. There was nothing registered in Australia in terms of their brand and trademark. That said, we probably took a little bit of liberty in terms of the designs. We wanted to have an association with people in America, but we also wanted it to be totally individual, as well.

“You know, with them taking the action that they took, that highlighted some things that we were probably a little bit too close to the sun and that we had to change, which is good,” he added. “Remembering that this was the first major event of this kind to have ever been done, and, you know, I was probably taking a few creative liberties at the time. Very rightly so, they called me out on it.”

The aspects of Bable’s operations that flew too close to the sun are easy to spot when reviewing the legal materials filed as part of SEG’s lawsuit, which focused on how the event was advertised in the local Australian media and in Blitz, a publication with international circulation. Referenced in the Papas affidavit is a full fight preview which appeared in the magazine, published in February 1997. It was titled “UFC Thunder Comes Down Under” and crooned that “the Ultimate Fighting Championships—is about to make its Australian debut.” The same issue featured a full-page advertisement superimposed on the silhouette of a fight that occurred at UFC 6, published without SEG’s permission.

Lion’s Den representative Matt Rocca was signed as an alternate in the tournament and got called up to the main bracket two weeks before the event.

“I was amazed that that marketing was actually able to take flight and hold for a while, because they were flat out using images from the UFC when they promoted it,” Rocca said. “When you look at the photo [advertising the event], it was a cartoon-strip kind of theme. It wasn’t exactly a still portrait or photo, but the image was clearly Cal Worsham and Paul Varelans slugging it out in the photo. To me, I was like, ‘I cannot believe that they’re actually able to use all of this material to market an event that has absolutely nothing to do with Semaphore Entertainment Group.’ I was absolutely astounded.”

* * *

The affidavits filed as part of SEG’s trademark proceeding and obtained by Sherdog provide a further detailed chronology of the steps the parties took in the days leading up to the event. Bable’s lawyers responded to SEG’s cease-and-desist letter, and formal settlement offers were exchanged by the parties during lengthy phone calls between their respective lawyers. All the while, Bable was busily tending to the staples of his inaugural fight week. They included overseeing the event’s press conference, rules meeting and “Meet the Fighters” press event, during which he would repeatedly distance his company from the “American UFC” that had been the subject of sustained criticism in the local media.

At the crux of SEG’s proposed settlement were undertakings prohibiting Bable from using the term “Ultimate Fighting Championship” and the offending logos and images in relation to the March event, future tournaments and in the packaging of the spectacles on VHS. While Sherdog was unable to obtain the precise undertakings, the Papas affidavit indicates that an in-principle agreement was reached between the parties on March 19, only for it to be withdrawn and supplanted by Bable two days later with a narrower set of commitments. The practical effect was circumnavigating SEG’s threatened injunction application, as narrated in the Papas affidavit, because the move came too late to approach the court.

“Negotiating over an extended period and agreeing to settlement terms with just the documents’ formal execution left to go ... then pulling back right before the event so there was not enough time for us to go back to court to stop them,” is how Isaacs described Bable’s “shady” tactics. “At the time, I thought our local counsel was outmaneuvered by believing Randy Bable’s lawyer was operating on the up and up. My sense was that they had let the clock run down intentionally, and—especially from 10,000 miles away—it seemed ridiculous that we had no recourse when they pulled out at the last minute.”

Asked to respond to Isaac’s hypothesis, Bable said, “I must have had good lawyers at the time.” Whether or not he was cunning, Bable’s tactics would serve only to delay the inevitable.

Four days after the openweight tournament, which saw Brazilian jiu-jitsu prodigy Mario Sperry crowned the inaugural Australasian heavyweight champion in front of a 5,000 strong Sydney crowd, SEG filed a 12-page proceeding against Bable and his company, alleging multiple breaches of the Australian Trade Practices Act. By way of interim relief, the application asked the court to temporarily restrain Bable from distributing the event on VHS and require him to deliver videos of the event and information on how many people had ordered the VHS and other merchandise to SEG. By way of final resolution, SEG sought orders permanently restraining Bable from marketing his promotion as the “Ultimate Fighting Championship” or the “UFC,” using the infringing logos, stating or representing any connection or affiliation with SEG or holding any event in an “octagonal fighting ring with a meshed surrounding fence.” In addition, SEG sought damages (with interest), compensation for legal costs and orders that Bable publish corrective advertising and deliver all promotional and other advertising material containing the offending phrases and logos to SEG’s lawyers.

“Any time that somebody put on a mixed martial arts event anywhere in the world, if anything went wrong, it was going to come back to us, and we didn’t need any more trouble,” Isaacs said. “It wasn’t just the loss of potential profits—that was part of it—but really, for us it was the confusion and something might happen and we would be tarred with the brush if anything happened. If the venue caught on fire, the headline would include ‘the Ultimate Fighting Championship.’ That was the situation.”

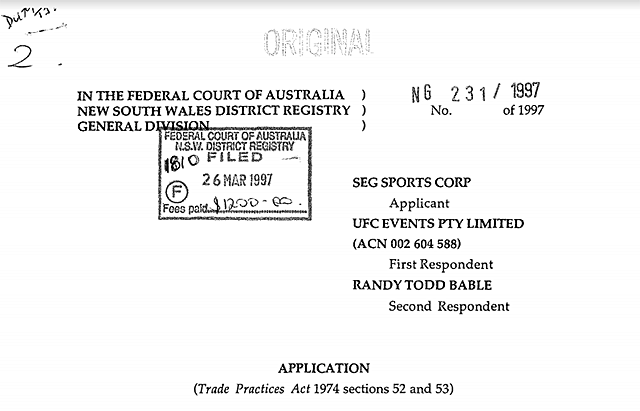

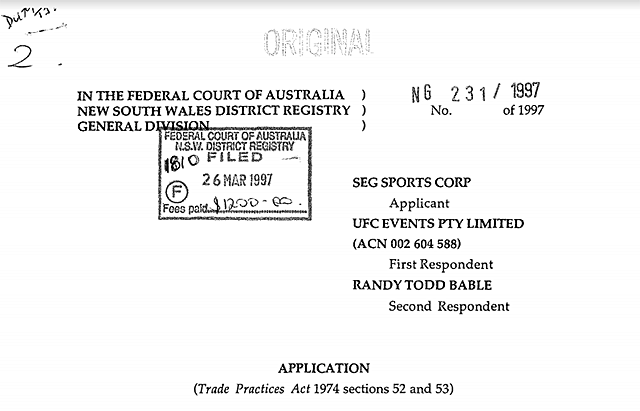

Cover page of SEG’s take-no-prisoners

trademark infringement lawsuit against

Bable. SEG would succeed in temporarily

restricting him from distributing VHS

versions of his March 22 event, but

ultimately lost interest in the case.

It was dismissed by Justice Tamberlin

of the Federal Court on Aug. 28, 1997.

Bable was nonchalant when asked how he reacted to reading SEG’s

take-no-prisoners application in late March, as he turned his mind

to post-production of the VHS. His only hope of recouping some of

his expenses on the event and paving the way to the next tournament

was slated for an October 1997 release.

“I just told my lawyers to deal with it,” he said. “Basically, that was it.”

Again, legal documents from the Federal Court proceeding set out the sequence of events following SEG’s application, filling in for the memories of the principals long since faded due to the passage of time.

In early April, Justice Tamberlin of the Federal Court of Australia accepted temporary undertakings from Bable agreeing not to distribute the event on VHS, use the infringing logos or phrases or use the corporate name “UFC Events Pty Ltd.”

A few weeks later, Bable’s lawyer, Jane Owen, lodged an affidavit purporting to refute SEG’s allegations of trademark infringement. Among Owen’s arguments were (1) the octagonal cage was a traditional martial arts symbol “represent[ing] the eight-fold path of Buddhism,” (2) Bable had clearly distinguished his event from the “American” UFC in media and promotional materials and (3) Bable implemented a more prescriptive—and discernibly different—ruleset.

Owen went on to stress the “substantial loss” Bable would be subjected to if the court further restrained him from distributing the videos or staging subsequent events, referencing $70,000 plus in losses he had already incurred. Marketing would be “impossible to calculate” if “no continuity in marketing” was maintained between the March tournament and future events. The olive branch was that Bable agreed to distribute the video under the new title “Caged Combat 1,” with the subtitles “Welcome to the Revolution” and “Australasian Ultimate Fighting Championship,” along with prominent disclaimers on the video wrapper and the opening segment of the tape.

Tamberlin did not subject Bable to further restrictions with respect to the VHS, releasing him to finalize post-production and begin pushing tape sales through Blitz and other distribution channels he said were on the table. The court also laid down a timetable for the parties to file further pleadings and affidavits between May and August, contemplating a trial where SEG’s allegations would be fully scrutinized and a final judgment rendered.

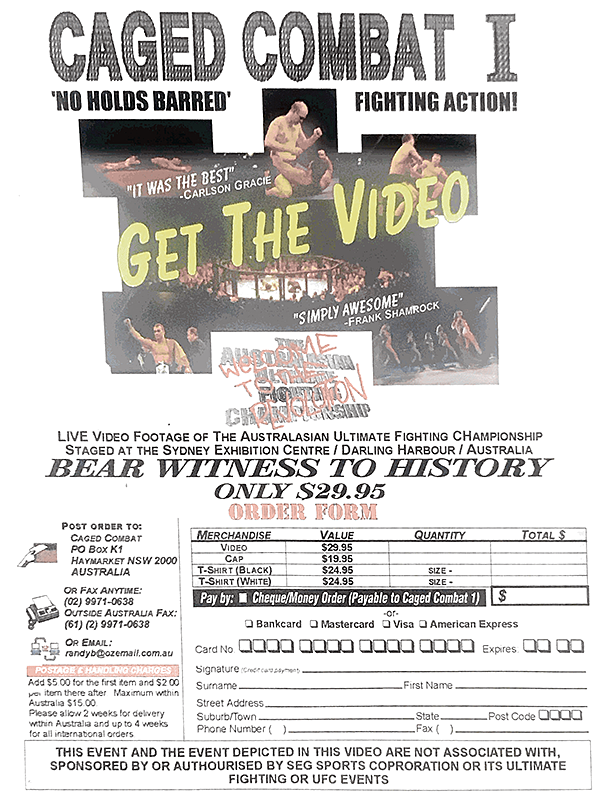

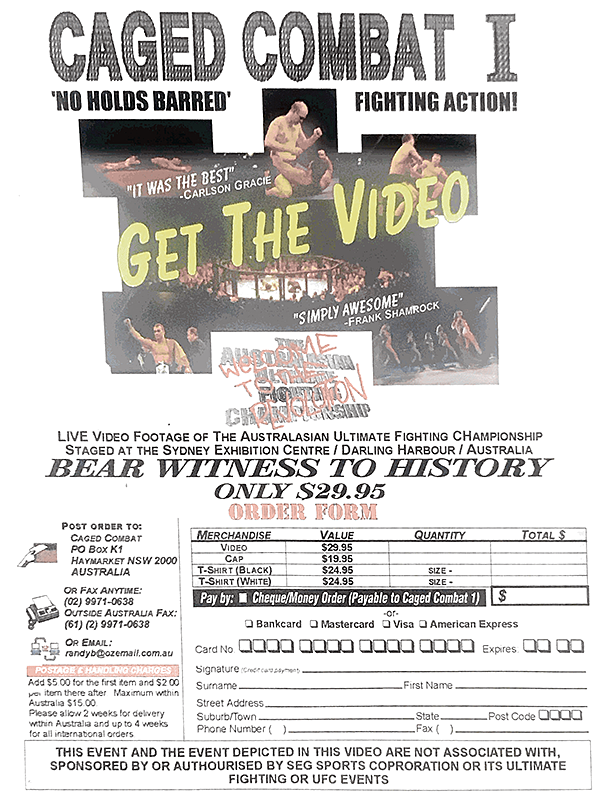

Order form for purchasing Randy Bable’s

NHB event, renamed “Caged Combat 1” to

accommodate Semaphore Entertainment’s

allegations of trademark infringement.

From Blitz Magazine (Vol. 11, Issue 5)

Perhaps sensing that its legal case was less of a slam dunk than it

had originally anticipated and struggling to keep afloat

financially after being dropped by pay-per-view providers back

home, SEG effectively disengaged from the proceeding after April.

In June, more than a month after the company failed to lodge a

statement of claim in accordance with the court’s timetable, SEG’s

lawyer ceased acting for it. Subsequent court dates were no-showed

by SEG, and the case was dismissed on August 28, 1997.

“When you’re really small, you don’t have any legal expenses,” Isaacs said, “but as you start to grow, you start to have assets that you want to protect. You have IP that you have to defend. If you don’t defend it, you lose it, so you get into this middle territory where it’s too expensive to defend your IP, but you can’t afford not to. … That was what led [Bable] to do this. The UFC was a big enough name for it to be worth it for him to put on this event. We were big enough that we had to try and stop it, but our resources were not infinite. We spent a sizable amount of money to go and do this on another continent. We were definitely really active in trying to stop it. You know, I’m not so unhappy that the event has been relegated to the dustbin of history.”

Continue Reading » Part 3: Barbarians at the Gate

Advertisement

THE SINCEREST FORM OF FLATTERY

For the Ultimate Fighting Championship owned and operated by Semaphore Entertainment Group in New York, this battle was one of many the organization waged at the time. After a brief honeymoon period of profitability and blue skies following the company’s runaway pay-per-view successes from 1993 to 1995, the UFC was buckling under the weight of politicians, cable operators and moralizing op-ed columnists. This was done in the name of protecting young, impressionable minds from a “lowest common denominator”—violence—which the UFC glorified above all else, proselytized then Arizona Senator and United States Senate Commerce Committee Chairman John McCain.

Many of the sport’s defenders would later speculate that, at least

for McCain, it was really about protecting boxing’s market share at

the behest of political donor Budweiser, boxing’s biggest

advertiser. More plausibly, it was a means for the senator to score

easy political points and remain at the forefront of the media

cycle. Whatever his motivation, the campaign impacted the future of

mixed martial arts by disrupting its present.

At the same time, on the other side of the world in Sydney, Randy Bable’s “Australasian UFC”—which he had incorporated in August 1996, with the hopes of jump starting an NHB franchise in the southern hemisphere—was navigating its own gauntlet of regulators, media naysayers and logistical hurdles ahead of its inaugural tournament event in the spring of 1997. Fervent discussions were ongoing with the Boxing Authority of New South Wales, which threatened to shut down the event, all while the eight-man openweight bracket was proving to be its own shape-shifting nightmare. Fighters dropped out left and right, and a succession of replacements were called up on short notice.

To avoid the political furor playing out in the United States, Bable aimed for what he considered a more streamlined, “professionalized” and regulated NHB product compared to SEG’s UFC. However, this was not going according to plan, and after he had already invested a quarter of a million dollars of his own money into the Sydney event, SEG fired the first salvo. The two organizations were brought into each other’s orbit via a cease-and-desist letter delivered to Bable’s office and the Darling Harbor Convention Center, where the tournament was supposed to take place in three weeks’ time.

“At this point in time, we were focused on staying alive,” recalled SEG Chief Operating Officer David Isaacs, who, alongside SEG President Bob Meyrowitz, was responsible for overseeing the company’s litany of lawsuits in America and abroad. “In the context of that, we kept having these competitors that would arrive on the scene and, in our view, potentially screw stuff up. That was what we were dealing with, and we had concerns about that from a lot of different perspectives. One was, we were focused on what we were doing as the Ultimate Fighting Championship, and we didn’t want anyone to be confused with us and put on a crappy event, or even worse, do something unsafe and get somebody hurt. That would hurt the whole sport but also our company. That was one thing that was going on around that phase. We’re scrapping for our survival, and everything we do is so, so important.”

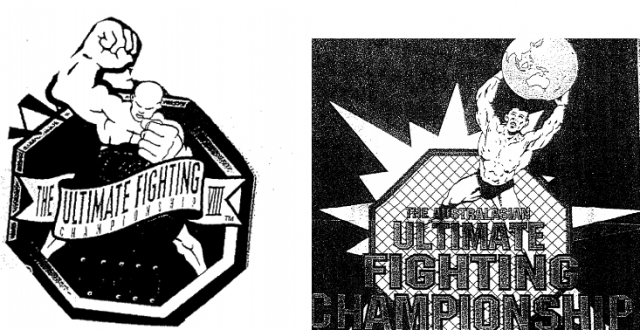

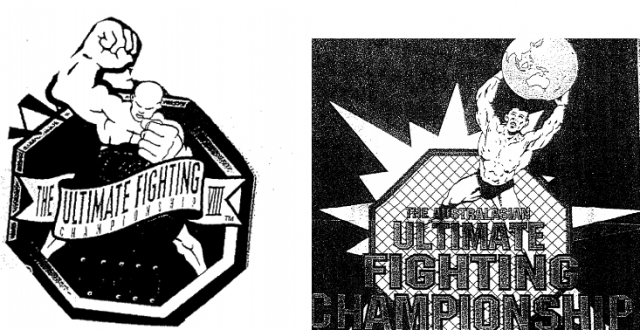

SEG

took issue with the logos Bable used to promote his “Australasian

UFC” event. It is not hard to see why when comparing Bable’s logo

(right) to the one SEG used to promote UFC (left). From the SEG’s

Originating Application filed in the Federal Court of Australia on

March 26, 1997, alleging Bable and his company breached the

Australian Trade Practices Act.

SEG executives were right to be mindful of the impact that competing promotions could have on the UFC’s increasingly precarious fortunes. Indeed, as Isaacs was quick to point out, the UFC 12 debacle in February 1997—which saw the UFC relocate its Octagon and fighters and staff from Niagara Falls, New York, to the Dothan Civic Center in Dothan, Alabama, on 48 hours’ notice—was due to the conduct of Battlecade Extreme Fighting, an NHB upstart three events into a four-event existence.

After SEG had spent more than a year lobbying to get NHB sanctioned in its home state of New York, a statute doing so was passed by the New York legislature. It placed the UFC under the purview of the New York State Athletic Commission. The UFC tentatively scheduled an event at the Niagara Falls Convention and Civic Center, far away from the scrutiny of the New York media and with the intention of building credibility and a constructive working relationship with the NYSAC.

Reckless or indifferent to SEG’s approach, Battlecade hastily announced it would hold a show smack dab in the middle of Manhattan, drawing the ire of New York Mayor Rudy Giuliani and setting off a chain of events that led the NYSAC to issue a 111-page rule book for NHB in an obvious attempt to backtrack on the legislation. A failed lawsuit brought by the SEG against the NYSAC challenging the new regulations failed and precipitated the mad dash south. The company was out another $300,000 it did not have, and the UFC’s New York aspirations were sunk in the process.

“In the midst of all that, here are these guys in Australia,” said Isaacs, who gets animated about the subject more than two decades later, “and they’re not just running a mixed martial arts event; they are literally trying to rip us off. They are using our name. They are using our octagon. They are literally using an image from one of our fights. They’re stealing our stuff.”

As narrated in a sworn affidavit by SEG’s Australian trademark attorney Spiros Papas obtained by Sherdog, the cease-and-desist letters accused Bable’s company, “UFC Events Pty Limited,” of various trademark infringements. This included the use of the octagonal cage and logos that were nearly identical to SEG’s and, most brazenly, passing itself off as the original UFC in its promotional materials published in the Blitz martial arts magazine. Further cease-and-desist notices were sent on March 14, 1997, triggering negotiations between the SEG and Bable’s lawyers. These discussions played out against an explicit threat from SEG that, if an agreement could not be reached, it would seek an injunction to stop the event from going forward.

“In Australia, nobody knew about [the UFC],” Bable said. “Nobody knew about it. Maybe point-one percent of the population knew what the thing was, so they really couldn’t argue that it was a known branding or a known trademark here in Australia. It’s a different country to America. There was nothing registered in Australia in terms of their brand and trademark. That said, we probably took a little bit of liberty in terms of the designs. We wanted to have an association with people in America, but we also wanted it to be totally individual, as well.

“You know, with them taking the action that they took, that highlighted some things that we were probably a little bit too close to the sun and that we had to change, which is good,” he added. “Remembering that this was the first major event of this kind to have ever been done, and, you know, I was probably taking a few creative liberties at the time. Very rightly so, they called me out on it.”

The aspects of Bable’s operations that flew too close to the sun are easy to spot when reviewing the legal materials filed as part of SEG’s lawsuit, which focused on how the event was advertised in the local Australian media and in Blitz, a publication with international circulation. Referenced in the Papas affidavit is a full fight preview which appeared in the magazine, published in February 1997. It was titled “UFC Thunder Comes Down Under” and crooned that “the Ultimate Fighting Championships—is about to make its Australian debut.” The same issue featured a full-page advertisement superimposed on the silhouette of a fight that occurred at UFC 6, published without SEG’s permission.

Lion’s Den representative Matt Rocca was signed as an alternate in the tournament and got called up to the main bracket two weeks before the event.

“I was amazed that that marketing was actually able to take flight and hold for a while, because they were flat out using images from the UFC when they promoted it,” Rocca said. “When you look at the photo [advertising the event], it was a cartoon-strip kind of theme. It wasn’t exactly a still portrait or photo, but the image was clearly Cal Worsham and Paul Varelans slugging it out in the photo. To me, I was like, ‘I cannot believe that they’re actually able to use all of this material to market an event that has absolutely nothing to do with Semaphore Entertainment Group.’ I was absolutely astounded.”

A

photo of Cal Worsham and Paul Varelans from UFC 6 (left) was used

in a promotional poster for the “Australasian Ultimate Fighting

Championship” (right).

The affidavits filed as part of SEG’s trademark proceeding and obtained by Sherdog provide a further detailed chronology of the steps the parties took in the days leading up to the event. Bable’s lawyers responded to SEG’s cease-and-desist letter, and formal settlement offers were exchanged by the parties during lengthy phone calls between their respective lawyers. All the while, Bable was busily tending to the staples of his inaugural fight week. They included overseeing the event’s press conference, rules meeting and “Meet the Fighters” press event, during which he would repeatedly distance his company from the “American UFC” that had been the subject of sustained criticism in the local media.

At the crux of SEG’s proposed settlement were undertakings prohibiting Bable from using the term “Ultimate Fighting Championship” and the offending logos and images in relation to the March event, future tournaments and in the packaging of the spectacles on VHS. While Sherdog was unable to obtain the precise undertakings, the Papas affidavit indicates that an in-principle agreement was reached between the parties on March 19, only for it to be withdrawn and supplanted by Bable two days later with a narrower set of commitments. The practical effect was circumnavigating SEG’s threatened injunction application, as narrated in the Papas affidavit, because the move came too late to approach the court.

“Negotiating over an extended period and agreeing to settlement terms with just the documents’ formal execution left to go ... then pulling back right before the event so there was not enough time for us to go back to court to stop them,” is how Isaacs described Bable’s “shady” tactics. “At the time, I thought our local counsel was outmaneuvered by believing Randy Bable’s lawyer was operating on the up and up. My sense was that they had let the clock run down intentionally, and—especially from 10,000 miles away—it seemed ridiculous that we had no recourse when they pulled out at the last minute.”

Asked to respond to Isaac’s hypothesis, Bable said, “I must have had good lawyers at the time.” Whether or not he was cunning, Bable’s tactics would serve only to delay the inevitable.

Four days after the openweight tournament, which saw Brazilian jiu-jitsu prodigy Mario Sperry crowned the inaugural Australasian heavyweight champion in front of a 5,000 strong Sydney crowd, SEG filed a 12-page proceeding against Bable and his company, alleging multiple breaches of the Australian Trade Practices Act. By way of interim relief, the application asked the court to temporarily restrain Bable from distributing the event on VHS and require him to deliver videos of the event and information on how many people had ordered the VHS and other merchandise to SEG. By way of final resolution, SEG sought orders permanently restraining Bable from marketing his promotion as the “Ultimate Fighting Championship” or the “UFC,” using the infringing logos, stating or representing any connection or affiliation with SEG or holding any event in an “octagonal fighting ring with a meshed surrounding fence.” In addition, SEG sought damages (with interest), compensation for legal costs and orders that Bable publish corrective advertising and deliver all promotional and other advertising material containing the offending phrases and logos to SEG’s lawyers.

“Any time that somebody put on a mixed martial arts event anywhere in the world, if anything went wrong, it was going to come back to us, and we didn’t need any more trouble,” Isaacs said. “It wasn’t just the loss of potential profits—that was part of it—but really, for us it was the confusion and something might happen and we would be tarred with the brush if anything happened. If the venue caught on fire, the headline would include ‘the Ultimate Fighting Championship.’ That was the situation.”

(+ Enlarge)

Cover page of SEG’s take-no-prisoners

trademark infringement lawsuit against

Bable. SEG would succeed in temporarily

restricting him from distributing VHS

versions of his March 22 event, but

ultimately lost interest in the case.

It was dismissed by Justice Tamberlin

of the Federal Court on Aug. 28, 1997.

“I just told my lawyers to deal with it,” he said. “Basically, that was it.”

Again, legal documents from the Federal Court proceeding set out the sequence of events following SEG’s application, filling in for the memories of the principals long since faded due to the passage of time.

In early April, Justice Tamberlin of the Federal Court of Australia accepted temporary undertakings from Bable agreeing not to distribute the event on VHS, use the infringing logos or phrases or use the corporate name “UFC Events Pty Ltd.”

A few weeks later, Bable’s lawyer, Jane Owen, lodged an affidavit purporting to refute SEG’s allegations of trademark infringement. Among Owen’s arguments were (1) the octagonal cage was a traditional martial arts symbol “represent[ing] the eight-fold path of Buddhism,” (2) Bable had clearly distinguished his event from the “American” UFC in media and promotional materials and (3) Bable implemented a more prescriptive—and discernibly different—ruleset.

Owen went on to stress the “substantial loss” Bable would be subjected to if the court further restrained him from distributing the videos or staging subsequent events, referencing $70,000 plus in losses he had already incurred. Marketing would be “impossible to calculate” if “no continuity in marketing” was maintained between the March tournament and future events. The olive branch was that Bable agreed to distribute the video under the new title “Caged Combat 1,” with the subtitles “Welcome to the Revolution” and “Australasian Ultimate Fighting Championship,” along with prominent disclaimers on the video wrapper and the opening segment of the tape.

Tamberlin did not subject Bable to further restrictions with respect to the VHS, releasing him to finalize post-production and begin pushing tape sales through Blitz and other distribution channels he said were on the table. The court also laid down a timetable for the parties to file further pleadings and affidavits between May and August, contemplating a trial where SEG’s allegations would be fully scrutinized and a final judgment rendered.

(+ Enlarge)

Order form for purchasing Randy Bable’s

NHB event, renamed “Caged Combat 1” to

accommodate Semaphore Entertainment’s

allegations of trademark infringement.

From Blitz Magazine (Vol. 11, Issue 5)

“When you’re really small, you don’t have any legal expenses,” Isaacs said, “but as you start to grow, you start to have assets that you want to protect. You have IP that you have to defend. If you don’t defend it, you lose it, so you get into this middle territory where it’s too expensive to defend your IP, but you can’t afford not to. … That was what led [Bable] to do this. The UFC was a big enough name for it to be worth it for him to put on this event. We were big enough that we had to try and stop it, but our resources were not infinite. We spent a sizable amount of money to go and do this on another continent. We were definitely really active in trying to stop it. You know, I’m not so unhappy that the event has been relegated to the dustbin of history.”

Continue Reading » Part 3: Barbarians at the Gate

Related Articles