Ben

Duffy/Sherdog.com illustration

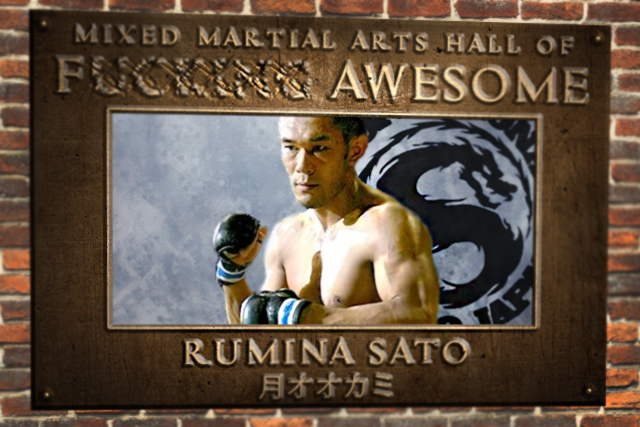

Headquartered in scenic Woodloch, Texas, the Mixed Martial Arts Hall of F@#$%&g Awesome (HOFA for short) commemorates the achievements of those fighters who, while they might not be first-ballot selections for a traditional hall of fame, nonetheless did remarkable things in the cage or ring, and deserve to be remembered. The HOFA enshrines pioneers, one-trick ponies and charming oddballs, and celebrates them in all their imperfect glory. While the HOFA selection committee’s criteria are mysterious and ever-evolving, the final test is whether the members can say, unanimously and with enthusiasm, “____________ was f@#$%&g awesome!”

Advertisement

—Rumina Sato

Though Sato delivered the preceding quote at the end of his legendary career, it could have been his mission statement from Day 1. Over the course of a nearly two-decade run in Shooto, “Moon Wolf” made his mark as a furiously aggressive, fearlessly creative, endlessly exciting submission specialist of the sort we may never see again.

While Sato exhibited an interest in martial arts from his teens,

interest did not translate into action until after high school,

when a gap year before university led him to begin training under

former Shooto champion Noboru Asahi.

After coming up through Shooto’s amateur system, Sato made his

professional debut at Shooto: Vale Tudo Access 2 on Nov. 7, 1994.

He won with what is probably the first calf slicer in mixed martial

arts history and just like that, the fundamental constants of

Sato’s fight career were in place, namely: He would be a Shooto man

for life, and we were going to see some eye-popping finishes.

Sato made good on that promise, establishing himself as one of the promotion’s top fighters and biggest stars without ever abandoning his trademark aggression or pace. As he did so, he became the poster child for the kind of freewheeling, submission-over-position grappling that exemplified 90s Shooto, and was one of the first fighters to present a viable alternative to the Gracie jiu-jitsu that had dominated MMA’s ground game since UFC 1. He also defied the stereotype that aggressive grapplers, when faced with their more conservative technical equals, would either be shown up on the ground, or forced into mediocre standup battles. At Vale Tudo Japan 1996, against John Lewis—another vital figure in the early history of MMA grappling—Sato fought to a draw that looked more like a loss, as he spent long stretches of the fight stuck underneath the bigger, stronger, more positionally sound BJJ black belt. In their rematch at VTJ 1997, Sato was every bit as aggressive, attacking with submissions from the bottom throughout the first round before catching Lewis with an armbar early in the second for the submission win.

As Sato cut a swath of heel hooks and flying armbars through Shooto, it eventually became impossible not to see him as something of an uncrowned king, and in fact he never did win a regular Shooto title in four tries. While that may be partly due to size—Sato was a small lightweight even by JMMA standards, and he was much the worse for wear by the time of his overdue drop to featherweight—it was mostly an issue of running into the wrong opponents at the wrong time, as Caol Uno and Takanori Gomi were probably the No. 1 and No. 2 fighters in the division from 1999-2001, when Sato faced them. It also essentially married Sato to Shooto for life. While he could easily have followed Uno to the Ultimate Fighting Championship, or Gomi to Pride Fighting Championships, Sato famously vowed he would never leave Shooto unless he won a belt, and when he won the Pacific Rim championship in 2005, it only appeared to bolster his resolve to keep seeking the world title.

By the time Sato finally dropped to 143 pounds, he was largely a spent force, but he received one last shot at a Shooto world title in 2009, when he drew two-time champ Takeshi Inoue despite a three-fight losing streak. The sentimental effort to get a belt for the man they had begun to call “The Charisma of Shooto” did not end well, as the younger, harder hitting “Lion Takeshi” put Sato away in the first round. That was it for title aspirations, though Sato fought on for a few more years. After his final professional fight in December 2012, representing his beloved art for the sixth time in the VTJ ring, he retired from MMA competition, transitioning directly into a role with the promotion and remaining sporadically active as a grappler.

SIGNATURE MOMENTS: In terms of professional accomplishment, Sato’s signature achievement was winning the inaugural Shooto Pacific Rim lightweight (145 pound) title on March 11, 2005. While Makoto Ishikawa is not the same kind of household name as some of the other legends on Sato’s ledger, he was a solid contender and deserving opponent. Sato won a wildly entertaining three-round scrap, marred only by a point deduction for an upkick to the head, to win the only professional MMA title of his career.

As one of the most entertaining fighters in MMA history, Sato has an embarrassment of riches when it comes to choosing highlights. He simply couldn’t help it; in July 2009, well into the final act of his MMA career, Sato appeared at the UFC Fan Expo ahead of the blockbuster UFC 100, where he faced future Tachi Palace Fights two-division champ Ulysses Gomez in a grappling match. Sato ended up winning with an inverted triangle wrist lock that looked somewhat like a heel hook without the heel…which should be impossible.

Yet that was Sato: at his best, he not only perfomed the impossible, but did it so quickly and made it look so easy that uninitiated viewers could be forgiven for asking, “Why doesn’t everyone just do that?” His early career win over fellow HOFA inductee Yves Edwards at SuperBrawl 17 was an eye opener, as Sato scaled the larger man like a ladder and took his back as he stood, then as the referee made Edwards let go of the ropes, slapped on a rear-naked choke. The two men came crashing to the ground and Edwards was tapping a few seconds later.

While the 18-second blitzing was the quickest loss of Edwards’ career, it wasn’t the quickest win of Sato’s. Facing Charles Diaz at Shooto: Devilock Fighters on Jan. 15, 1999, Sato stalked across the ring, ducked through Diaz’s first couple of strikes, and grabbed an elbow and collar tie, the textbook launch pad for a million catch wrestling techniques. He then leapt into the air, transferred his grip to Diaz’s right wrist and secured an armbar. Diaz was trying to tap before they even hit the ground, and it was all over in just six seconds. While there have been other flying armbar submissions in MMA, including quicker ones, there may never have been a more perfect one. Diaz got up shaking his head in confusion, and everyone watching knew exactly how he felt.

THE HOFA COMMITTEE SAYS: Sato is a prime example of a fighter who was much more, and who meant much more to the sport, than his straight wins and losses would seem to indicate. As an MMA pioneer, a fantastically entertaining grappler and—with all due honor and respect to Yuki Nakai—the man most synonymous with Shooto, “Moon Wolf” is a true legend of the sport. His highlight reel is one for the ages, but more importantly, a highlight reel is almost unnecessary, as Sato managed to navigate a 45-fight career without ever seeming to give us a dull moment. His importance is evident from the kind of people who pay him tribute: From fellow MMA pioneer Marloes Coenen taking his name for her nom de guerre, to longtime UFC matchmaking wizard Joe Silva naming his cat “Rumina Gato,” those who know, know.

It is with great pleasure that we say: Rumina Sato, you are f@#$%&g awesome.

« Previous The MMA Hall of F@#$%&G Awesome: Megumi Fujii

Next The MMA Hall of F@#$%&G Awesome: Jose Landi-Jons »

More

The MMA Hall of F@#$%&g Awesome

The MMA Hall of F@#$%&g Awesome